For some years, I've collected information about the noted unionist and coalfields historian Jim Comerford, a longtime resident of the Hunter coalfields town of Kurri Kurri, in the hope I could write some sort of biography.

Mr Comerford passed away on November 2, and I think it's worth republishing excerpts from an article he wrote for the union magazine Common Cause of September 27, 1997, seventy years after the day he went down the pit as a 14-year-old boy:

In August 1927 I was withdrawn from High School at the age 13. This blow was softened by an office boy's job at the Kurri Times, thanks to the recommendation of Mr J. Henry, Headmaster at Kurri Primary School. The job paid $1.50 a week.

I had dreams of a brilliant career as a journalist and writer. These were soon shattered when I arrived home from work at the Times on my 14th birthday. My father told me that I was to start the next day on afternoon shift at the Richmond Main coal mine.

Only strict parental control kept me from rebelling. There was a dread in me about coal mines. Too often we had gazed out of school windows as miners slowly marched by to bury their dead.

* * * * * *

My parents' decision to send me to work in the mine was driven by family hardship. We lived in a poor rented place. On the north side of town, a new home was being built for us. Richmond Main would pay me 78 cents a shift, against the Kurri Times's 30 cents. Every cent was needed to pay for that beaut new home.

So, on Wednesday 27 September, clad in black shirt, pit boots, old pants and a cloth cap, carrying my crib tin and water bottle, I was taken to the company train at Pelaw Main Colliery terminal. In its austere carriages were the 250 men and boys who would follow the 1000 men on day shift at “Baron” John Brown's super mine, Richmond Main.

* * * * * *

All that night the off face blokes came to talk to me. In their friendly way they explained what those underground workings were all about. So did my four wheelers as I opened and closed the doors for them.

Early in the shift I was startled by what I was sure was the sound of an explosion. But it was the face miners and shot firers at work.The powder fumes drifted back to mix with the other humid pit smells I was absorbing.

The worst experience that night was to see the axe-dismembered body of a dead pit horse being sent out of the stone drive.

Nobody called me by name. They called me “trapper”. Every child-worker on ventilating doors in the pits was called trapper.

By shift's end, this trapper, tired and dirty, had already changed from the fearful one who waited at the brace earlier that shift. The change was completed on pay day when I was led to the Stump cabin and impressed with the imperative about being a Union boy.

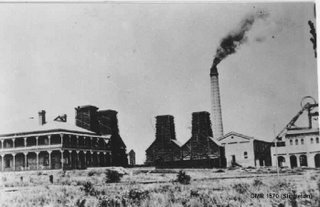

The photo shows Richmond Main as Jim Comerford would have seen it from the train:

Jim Comerford remained a staunch unionist all his life – understandable for the son of a Scottish miner who brought his family to Australia in 1922 to escape victimisation on the East Fife field. From pit boy, Jim Comerford rose to be general secretary of the Miners' Federation, and he represented his union on overseas delegations and many government inquiries.

But he was more than a unionist. He typified what historian John Hirst has called the self-improving working class, involved in adult education and a wide range of welfare and cultural causes in the tightly knit mining communities.

I encountered his writing when I picked up Mines, Wines and People, published in 1979 by the Greater Cessnock City Council. In it, WS Parkes gave a detailed history of the landholders of 1821 to 1856 and Dr Max Lake offered a history of local wine-making.

For me, however, the section which stood out was Jim Comerford's account of the dramatic rise and decline of the South Maitland coalfield around Cessnock and Kurri Kurri, its disasters and disputes, and the social cohesion of its mining communities.

After the Mines, Wines and People section, he wrote Coal and Colonials.

In Mines, etc, he gave just over four pages to the coal industry's worst dispute, the lockout which began in March 1929 and ended 15 months later – a dispute which included the Rothbury riot, where police (Comerford is adamant it was police) shot dead the young miner Norman Brown and injured many others, some by gunfire and some by bashing. He said the lockout deserved a book to itself.

As a 16-year-old, Jim Comerford witnessed the Rothbury riot. And this year, three-quarters of a century later, he delivered that book – Lockout.

A lifetime Kurri resident, Mr Comerford seems not to have achieved much recognition outside the Hunter Valley. He did, however, receive an Order of Australia, as well as an honorary MA from the University of Newcastle for his lifetime of scholarship.

Perhaps it's drawing a long bow, but here's a thought – his father's ordering young Jim down the pit may have deprived Australia of a journalist, writer and historian who would have grown to the stature of C.E.W. Bean.

A recent check with ABE Books showed secondhand booksellers offering Mines, etc from $29.30 plus postage and a lone US seller with Coal and Colonials at $40.55. Lockout can be ordered from the CFMEU union (02 9267 1035) for $35 including postage.

Jim Comerford also gave a short reminiscence of his first day at Richmond Main in Beneath the Valley, a collection of mining stories, poems and memoirs published by Newcastle's Catchfire Press.

Richmond Main is preserved as a heritage site, and it's a great place for a family outing.

No comments:

Post a Comment